I ‘m often asked about the relative merits of using oak barrels to add a flavor dimension to wine. Does the oak do anything to actually improve the taste? Doesn't using oak just inject an artificial element into a naturally produced product? Can oak be used to age both red and white wine? These are just a few of the more commonly asked questions regarding the ancient relationship between wine and oak which I will explore for you today. (Also, see my own oak wine barrel at my house and on-camera musings on this subject on the latest 'WineBoy' webcast, online this Wednesday).

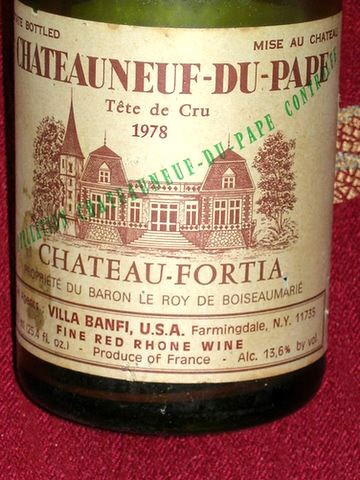

While historians can't pinpoint when the first wooden barrel was produced (some credit the Celts in ancient Burgundy in 1300 BC), those ancient vessels were simply a utilitarian method of storage and were not seen as adding any complexity or nuance to the wine. However, for the past century or so, vintners have been using different types of oak barrels to influence the flavor of the wine inside them. Today, oak trees grown here and abroad are used to make the barrels holding some of the world's greatest wines.

Limousin and Nevers are famous types of French oak which are used to make very expensive barrels in which cabernet sauvignon and chardonnay are aged. American white oak from Missouri, Kentucky and Arkansas is also used by wine makers around the world to age their wines. In fact, wine makers have discovered that certain types of oak impart pleasant taste and smell characteristics to wine, particularly when the inside of the vessel is charred over a fire burning the same wood used to make the barrel. These barrel makers (or coopers) are very skilled in charring the inside of the vessels with either a light, medium or heavy toasting – depending on the wishes of the wine maker.

Incidentally, the use of oak also comes with a price since most wines, particularly ones aged in French oak, are more expensive. The cost to produce a 60-gallon Limousin barrel can exceed $2,000. That hint of vanilla in a fine Bordeaux or cabernet or that toasty, buttery bouquet in a good chardonnay are examples of how the proper application of oak aging can positively influence winemaking.

So where do I stand on the issue of oak aging? Well, if you’ll bear with me a few more paragraphs, I think a short digression will answer the question. When I was a child (sometime after the Korean War but before John Kennedy became president), my grandfather would regularly direct me to fetch a jug of wine from the earthen cellar he had dug in the basement of his home. It was in this dark and dank room where he made strong, red wine that was aged in large oak barrels. Illuminated by a single hanging bulb, the room was cast in an eerie half-light and smelled of damp earth, pleasantly sour fruit and old wood. It was a mysterious place -- a solemn enclave where the fruits of my grandfather's labor lay in serene harmony within the old oak barrels.

Those oaken casks worked their magic by imparting to the wine inside them a round and supple texture. This allowed the wine to be consumed and enjoyed after about one year of aging. According to my grandfather, "It is the natural way of things." Those barrels, now long gone, held a special fascination for me, and etched forever in my mind the indelible view that oak aging is an essential step in the process of turning grapes into good wine.

It should not be surprising then that, when I began to make my own wine a few decades ago, my first purchase was a small, 15-gallon American oak barrel. Since a 60-gallon barrel is considered small by today's wine making standards, I was aging my first vintage California zinfandel in a mini-cask where the ratio of wood to wine was very great. This, of course, was the metaphorical equivalent of swatting a gnat with a telephone pole. After six months in the barrel, the resulting beverage tasted like liquid oak with hints of red wine! I have since learned to be more moderate in the application of oak to wine.

However, some people feel that oak-aging is nothing more than an unnatural intrusion in the wine making process, and adulterates the true taste of wine. And indeed, some heavy handed wine makers overuse oak (just as I did the first time I made wine) and the result can be disastrous.

To oak or not to oak? That is the question dear Bacchus… and that's what makes this whole wine appreciation thing so much fun! My choice, though, was made years ago in that subterranean room with the earthy smells and the ancient barrels that held my grandfather's labor of love.